Carla Grunauer:

LA ORILLA SENTIMENTAL

30 JUL ↭ 10 OCT, 2025

EXHIBITED WORKS

Text by Juan Laxagueborde

In this exhibition, which you’ve seen or are about to see, Carla Grunauer returns to curved lines and open motifs to acknowledge the difficulties of expression without needing to resort to expressionism. Expression is a tremendous word—variable and habitual. It’s like verbal language: we speak without entirely knowing. We speak or act in order to know. Everything is expression; it’s inevitable.

It feels to me like what’s here aren’t portraits, characters, or superheroes. They’re more like objects, figures, feints, or faces for finding souls—if that word can even be said just like that. These aren’t cyborgs, but humanist paintings with what little remains, as Felipe de la Fuente or Knaum Knop taught us. All of this takes place in a room that feels like a subdued quinceañera party or a leveled-out living room.

Maybe at the junction (the edge) of that brown with that neighboring blue, there’s another brown and another blue. This means the scene is one of suspicion, of change, of calm intuition, covering and uncovering what we don’t know.

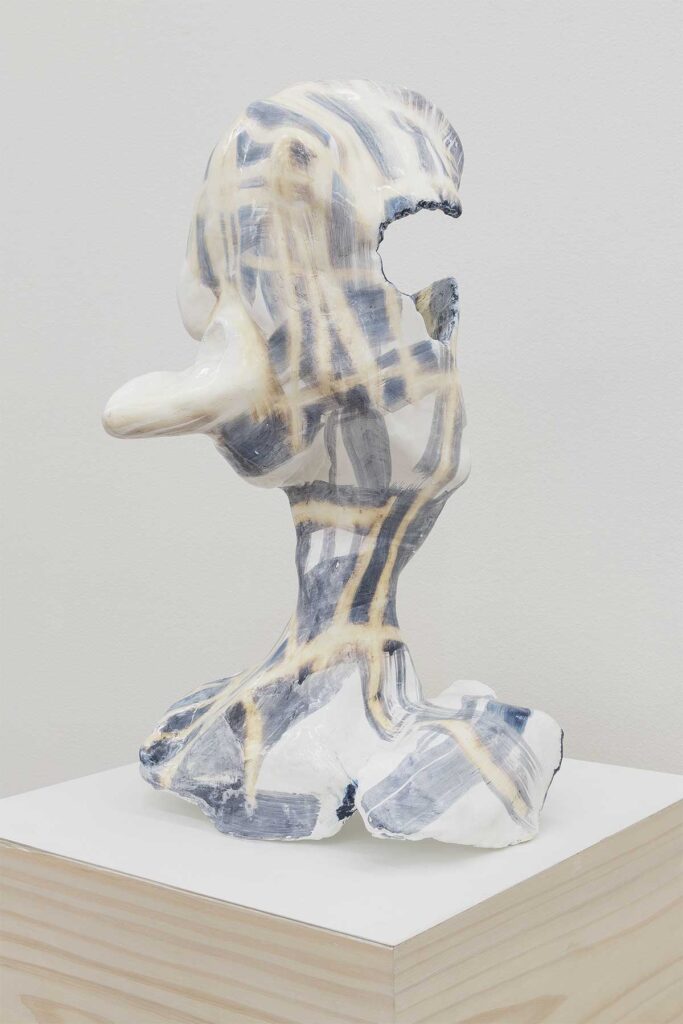

In the sculptures, she calls the three-dimensional pop—because pop is the mix of the popular and the strange. Then there are the ones lying down, like patients on a therapist’s couch whose notes we can snoop into, though we can’t read the handwriting. We don’t know if they’re resting, depressed, about to get up, or gathering focus to leave.

Usefulness is the use of uselessness, and another way of saying this is that Carla’s painted figures are absorbed into abstraction—and vice versa.

The painter and more, Francis Picabia, used to tell anyone willing to listen that the head is round so that thought can change direction. That phrase is one of Carla’s favorites. She once wrote a text about her practice that begins by invoking that phrase and is titled “Hilarious in its Structure.”

(I wouldn’t want to speak of references, but rather of memories. Almost everything is a memory, because even reason is a feeling.)

Structures are what necessarily remain, like the empty lot in a town once the circus leaves. They serve to find the glove of occurrences and desire. It doesn’t matter what for—that’s another issue.

Like all wall texts, this one tries to have a conversation with the people walking through the exhibition. The paintings, the sculptures, and the text tend to follow their own paths, so the problem is circular—in the sense of repetition, but also of movement, of going from one point to another with a certain orientation, or moving because we don’t know where we’re going and we’re happy, normal, sad, persistent, pale, aimless, idle—even because we have nowhere to go…

The possibilities combine into an infinite entanglement. The circuit of feeling is unpredictable. No one knows what will become of us. That background of unbeatable, everyday, special uncertainty can only be endured because we share it with everyone who has passed through this place. I don’t mean Galería Piedras or San Telmo or Buenos Aires, but the planet, since time began.

Limit, structure, and edge are part of the same series—only the edge has a more diffuse connotation, a temporary sense of separation, like a fence that could be moved a few meters forward or back by the grace of the moon embedded in the metal, in an alliance between sky and ground that become friends, accomplices, and militants of the land itself, conspiring so that one day we wake up and the limits—what’s supposedly ours—are understood as products of others. By “product” I mean result, sometimes a fatality, an effect, a collaboration, and why not, a work of art. Just by thinking of it, the sense, the instrumentality, the “why” begins to blur.

Life as a work of art—though what’s still missing is a fairer redistribution of the bread, the fish, the housing, the wages, and the works of art themselves, which will continue to exist to do us good, to rid us of fear, or to help us recognize the contempt some have for existence.

The fence was invented in the 19th century, and before the 19th century, there was injustice; afterward, there was still injustice, but there were also some strong ideas of the future that stirred enthusiasm to the point that the word avant-garde moved from war to the battle for sensitivity.

But let’s not lose heart—we still have the past to interrogate with invented questions that are not easy to ask. We still have the outskirts of dreams, and we still have artists like Carla.

It seems to me that Carla always returns to the outer edges of images: she searches in the depths of the history of territories, in the runes we know even without ever having seen a photo of them—because they’ve been carried over into design, language, and social customs. But she also investigates precise areas of an image to look there for another image, another reference, another stimulus that echoes the previous one—a very distant or neighborly memory. One image more, which includes the one she saw before, and lets us glimpse the future of images as a future of succession, equivalence, translation, and inheritance that justifies—without pomp and with patience—art itself.